Resources

A collection of free resources to help you raise funds and share the work we do

By Michael Grey

It must be be quite difficult, in an era of rapid technological change, for seafarers entering the profession to assess what the future of shipping is likely to bring. Just think what today’s senior officers have seen during their career span! And an even earlier generation would have had no idea about the impact containerisation, satellite navigation, automation, worldwide communications, or the explosion in ship sizes and dimensions, would have.

Some have likened it to the astonishing effect that power-driven ships had upon the slow evolution of sailing ships over millennia. It took unusual imagination in the beginning of the 19th Century to believe that the first halting experiments with steam at sea could ever preface such a revolution.

The truth is that you might make semi-informed guesses as to what the future will bring, but most people did not see many of these dramatic changes coming, even though they would completely change the face of an old, essential, and hugely international industry. You might, to use the terminology of the weather expert, suggest that the forecast remains largely ‘uncertain’. And these days, the technological weather can change very rapidly indeed.

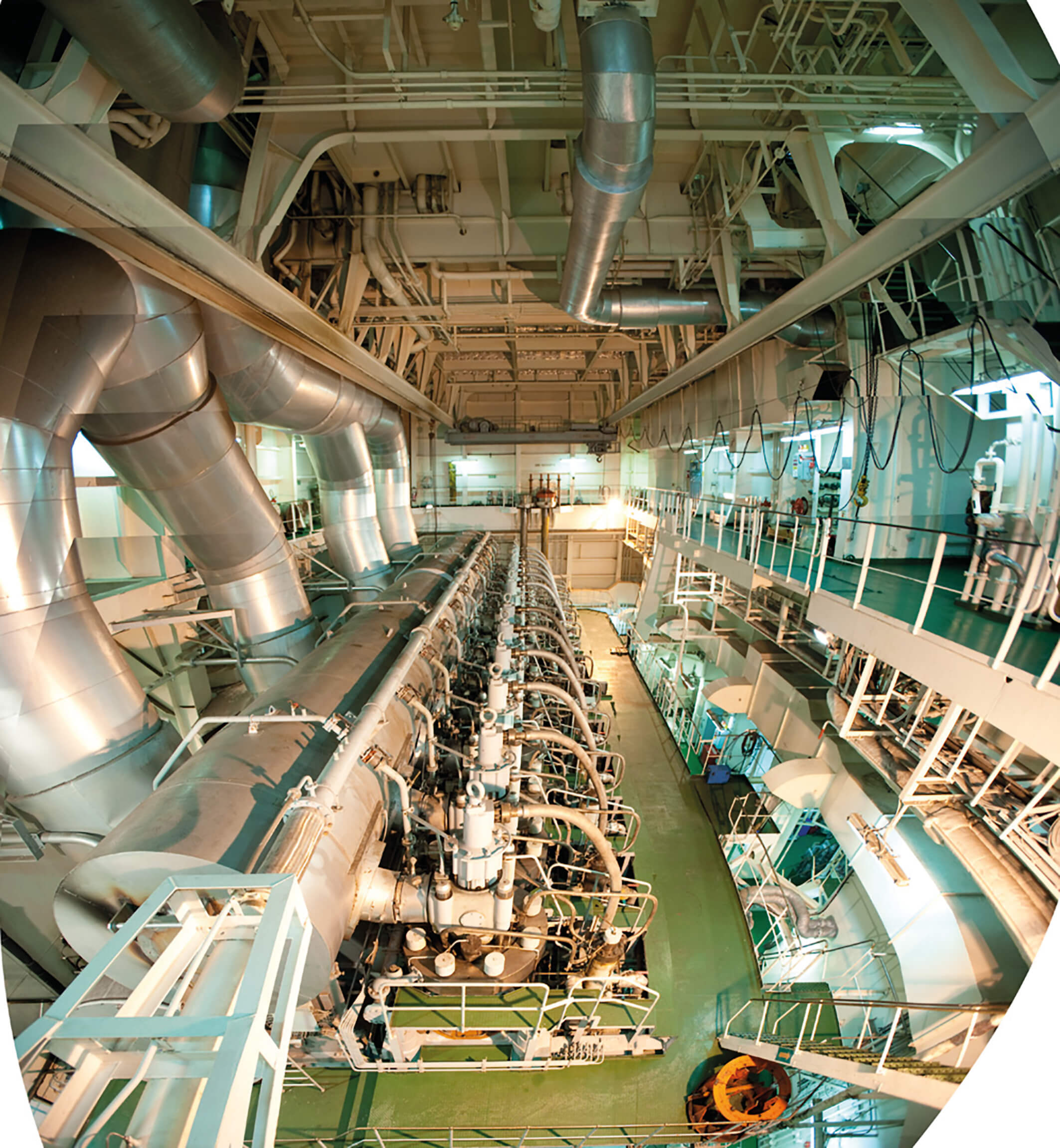

There is very little we can be sure about in our efforts to suggest what might lie over the horizon for today’s seafarers. We might be fairly sure that the quest for ‘net zero’ shipping will not go away, and the search for more sustainable ways of carrying seaborne trade around the world will govern a great deal of design and engineering thinking in the coming years. Might the era of the great, powerful diesel engine be drawing to its close, or will new design breakthroughs, aided by new and sustainable fuels, enable the efficiencies and power of internal combustion to live on? We might guess that right across the board there will be different fuels, combustion processes, and technologies all competing to demonstrate, eventually, what will be the dominant system or process, to produce the cleanest, greenest mode of maritime transport.

Quest for autonomy

A great deal of current attention is being paid to autonomy, and the suggestion that the control of ships at sea can be accomplished remotely, by technicians (can they be still termed seafarers?) operating in control centres ashore. It is difficult to even hazard a guess as to where this will all go, but experienced seafarers suggest that the brains (and sometimes brawn) of seafarers will always be needed to keep complex structures like ships running, in a hostile environment, a long way from home.

It is even quite difficult to take a guess at the sort of skills which will be needed by future seafarers. More electrics and electronics, more complex and interlinked systems, more sophisticated communications and data transmission, and new methods of propulsion, from nuclear to a greater use of the wind, would suggest that seafarers will be as adaptable as ever.

Far greater reliance on regular skills upgrading and through-career training would appear to be indicated – a challenge for maritime education going forward. There might be old lessons to re-learn, such as the best way of using the trade winds and the oceanic currents to help ships along, in the most sustainable way of all.

Some things just won’t change. The sea will always remain the greatest challenge, no matter how clever the ship designers and seafarers of the future are. The very best ships, constructed of the most expensive materials and crammed with the most sophisticated equipment, will experience wear, the effects of a fierce, corrosive environment and all that heat, cold, vibration and violent motion can throw at it. Things will break down and accidents will happen. The sea, for sure, won’t give up.

Seamanship and marine engineering, sciences which have always evolved to suit the current generation of ships and seafarers will surely still be needed, in whatever form they may require.

Adaptability will be the key.